Zephyr Penoyre

I work on galactic dynamics through a variety of approaches, with a focus on the galactic centre of our Milky Way, and on hypervelocity stars. Our recent work has highlighted the importance of large scale chaotic galactic orbits that can occasionally dive very deep into the center of the galaxy, close enough for the system to be disrupted by the central massive black hole. This provides a novel and potentially dominant channel for tidal disruptions.

Chaos in galactic potentials

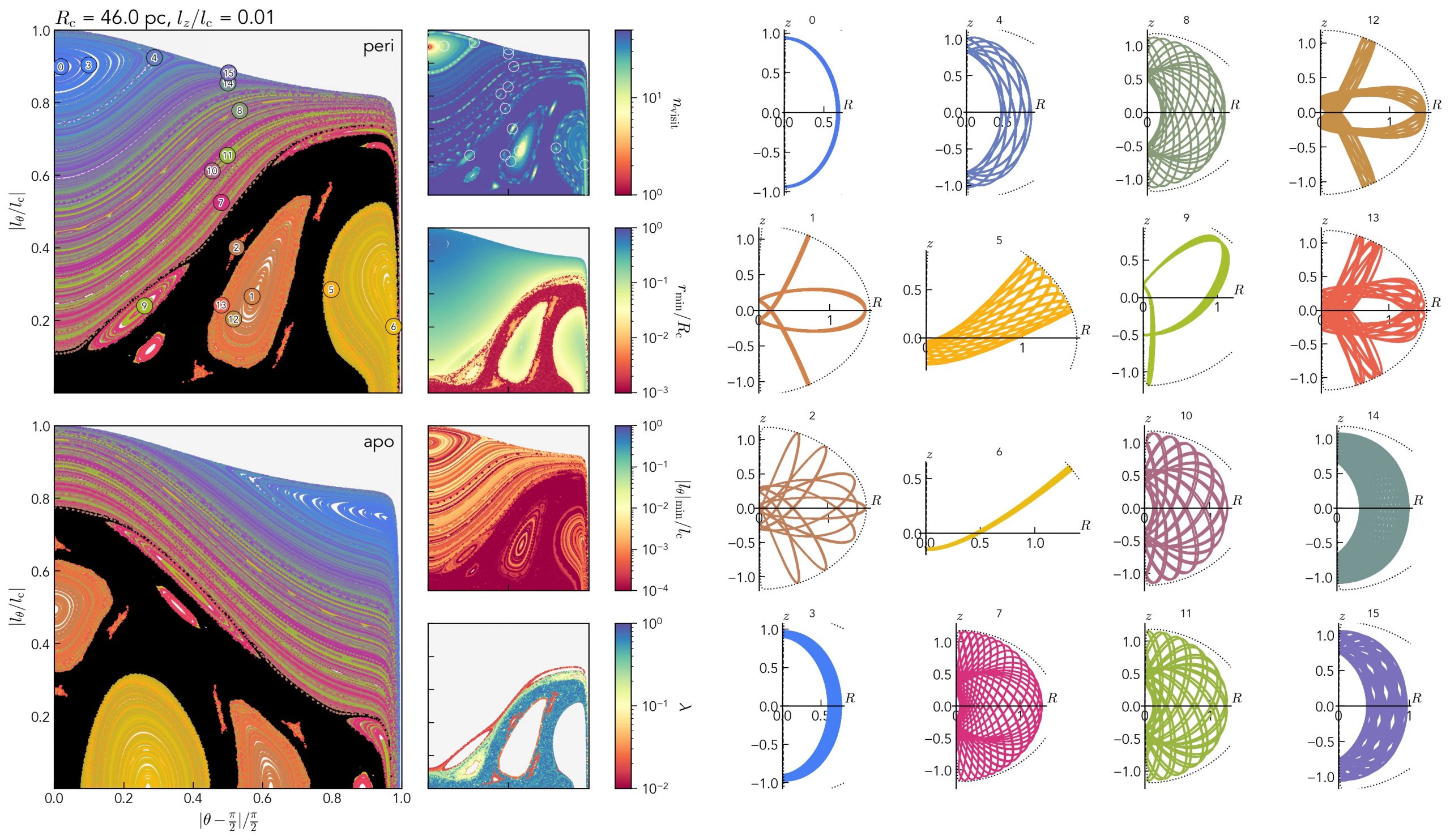

Orbits in a non-spherical potential can be much more complex then their spherical counterparts, allowing a wider range of physical behaviours and outcomes. Here we show all of the possible orbits, at a given energy, in an axisymmetric model of the center of the Milky Way. The left hand plots show the non-conserved component of angular momentum, and the polar angle, at periapse (top) and apoapse (bottom). The colours are set by the initial conditions and 16 of the thousands of orbits integrated are shown in the right-hand panels – chosen to represent some of the major orbit families and their harmonics. For example the orbit labelled 1 is a reversible orbit (in that it turns and doubles back on itself) with 2 distinct kinds of apoapse – it is often called a fish orbit – and orbits 2, 12 and 13 are all harmonics of this basic orbit.

Orbits coloured in black are chaotic – they do not show regular repeating behaviour and explore a wide region of space – including the lowest possible angular momenta at periapse (along the bottom axis of the plot). These orbits can pass very close to the central Massive Black Hole (MBH), and can be disrupted, giving energetic transient observables like EMRIs, TDEs and Hypervelocity Stars (see the work of other group members!).

We call these ‘diving orbits’, because they spend much of their life at large distances from the MBH but occasionally dive very close to it. This is a very different population from other systems which are likely to be disrupted, which tend to orbit very close to the MBH and are perturbed onto orbits close enough for disruptions by scatterings with other stars. Our preliminary work suggest that diving orbits may be a significant, perhaps dominant, contribution to the total rate of disrupting stars and binaries, and that the degree of asymmetry of galactic centers and the ubiquity of chaotic orbits may determine how frequently we should observe the high energy transients associated with these disruptions.

Hypervelocity Stars

The extreme mass and (relatively) small scale of a supermassive black hole (SMBH) like the one at the center of our galaxy leads to incredibly high energy dynamics – close encounters with it can tear objects apart and give the remnant enough velocity to leave the galaxy – we study the (classical) dynamics problems posed by the motion of stars near such an object, particularly of binary stars, whose three body interaction with the SMBH can split the pair, leaving one on a close orbit around the galactic center and the other flying out with huge velocity – these HyperVelocity Stars (HVS) are observable as they make their way out from the galactic center, and thus carry information about that very small and shrouded region into an observable location as well as studying the intricate dynamics of the interaction itself it is important to understand how systems come to be on orbits that come so close to the SMBH – to do this we study the chaotic families of trajectories possible within the center (<100 parsecs) of the galaxy – which are affected by the galactic bulge, nuclear stellar disk and cluster, and the SMBH itself – thus once again linking the properties of the galactic center to an observable output.

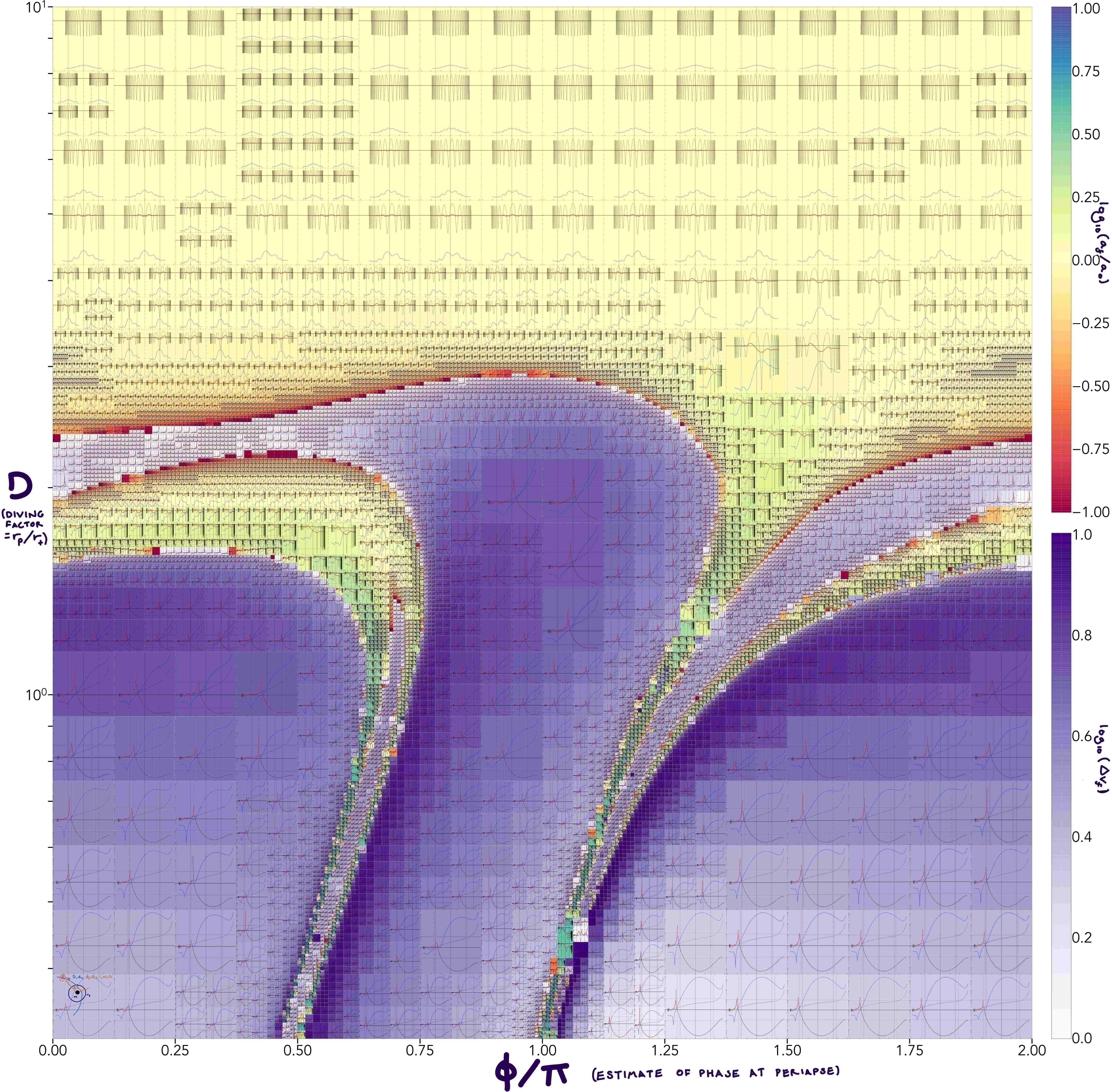

In this figure, a grid of all the possible evolutions and outcomes of an encounter between a binary star (with initial eccentricty of 0.3) and a SMBH, dependant on the diving factor (y-axis, the ratio of the distance of closest approach to the distance at which we’d expect a disruption) and the initial phase of the binary (x-axis) – every subplot shows the evolution of the radius (grey), semi-major axis (red) and eccentricity (blue) throughout the encounter, as a function of time, with the time of closest approach marked as a vertical black line – the color of each subplot shows the ejection velocity (purples) if the binary is disrupted, or the relative change in the size of the binary orbit if the binary survives (reds and oranges show binaries that get tighter, yellow shows binaries that don’t change, and greens and blues show systems where the binary is enlarged).